There are many different theories on how and why people develop fears and phobias. These theories are formed from various perspectives such as biological components, behaviorist explanations, cognitive components, an attachment and psychodynamic explanation and a holistic theory. We will focus solely on the behaviorist approach and how learning plays a role in the expression of fears and phobias by discussing concepts such as classical conditioning, operant conditioning, the social learning theory, and positive and negative reinforcement.

To understand how learning contributes to the expression of fears and phobias it is crucial to first explore what fears and phobias are and the difference between these concepts. Fear is an emotional response to a perceived threat, that prepares an organism for the freeze, flight, or fight response to deal with the perceived danger to survive (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023). For example, when suddenly observing a snake, a variety of psychological changes occurs such as increased heartrate and breathing. However, fear is not only a psychological response, but also affects an individual’s behavior, and it has emotional and cognitive consequences and affects a person’s thoughts and feelings (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023). On the other hand, a phobia is a disproportionate fear response to a specific object or situation, and it might have a wide range of crippling effects on an individual’s well-being and life quality (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023). For example, a person might have a phobia of germs, mysophobia. These people might clean obsessively and might be in a constant panic when leaving their homes. In addition, social anxiety is an intense fear of socializing and meeting new people and it stems from a fear of saying or doing something embarrassing and being judged harshly for it. Specific phobias and social anxiety disorder are both subsidiary of the umbrella term anxiety disorders. When distinguishing between fear and phobia it is important to consider how frequently it is experienced, how long the reaction lasts and if the reaction and its intensity is in proportion to the threat (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023).

Behaviorists argue from the perspective of nurture, and they believe that fear and phobias have their origins from experience and environmental influences. One such theory that sheds light on how fear and phobias might be obtained is classical conditioning. Pavlov (1927, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023) discovered that if a bell is repeatedly rung when dogs receive food, the dogs associate the sound of the bell with food, and they will later salivate when hearing only the sound of a bell. The dogs learned a new behavior that was not previously present. This theory can explain why people develop phobias. For example, cynophobia, the fear of dogs, where perceiving dogs start off as a neutral stimulus which doesn’t evoke a fear response. When a traumatic event, such as a being attacked by a dog occurs, perceiving dogs then gets paired with pain and trauma. Now, by just observing a dog can bring about a fear response. Dogs, by themselves, have now become the conditioned stimulus and the fear reaction to dogs has become the conditioned response. This might explain how some phobias are acquired but cannot explain why phobias persist, because of the evidence of extinction, which means that a conditioned response fades quickly, and must continuously be re-paired to persist (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023).

Currently, classical conditioning is used in the treatment of phobias using the principle of counterconditioning and is called exposure therapy. In other words, the fear response can be replaced by a new conditioned response by continually paring the fear stimulus with a positive association. Systematic desensitization is one such treatment and is developed by Wolpe (1961, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023). This treatment consists of various stages which become progressively more anxiety inducing. For example, a person with a fear of spiders, arachnophobia, would start off by looking at images of spiders. Then they might imagine themselves observing a spider, then actually being in the presence of a spider and finally touching the spider. The person will first learn calming techniques because for the treatment to be successful the person is required to stay calm during each stage to move on to the next. If the person can stay calm in the final stage, the phobia has been overcome. People don’t only acquire phobias through learning but also overcome them by learning or rather unlearning.

In his two-factor model theory, Movrer (1951, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023), found that classical conditioning might explain how we acquire phobias, but operant conditioning may give insights into why phobias persist. In the earlier example, people with cynophobia will avoid situations where they might get into contact with dogs in the future, such as avoiding parks or going to a dog owner friend’s house. This short-term reward of this avoidance behavior in turn strengthens the fear of dogs. The continued avoidance of the unpleasant experience then strengthens the fear itself. This is an example of negative reinforcement. Although this can explain the root cause of some phobias and how they persist, not all phobias have their origins form a negative experience and need an additional explanation.

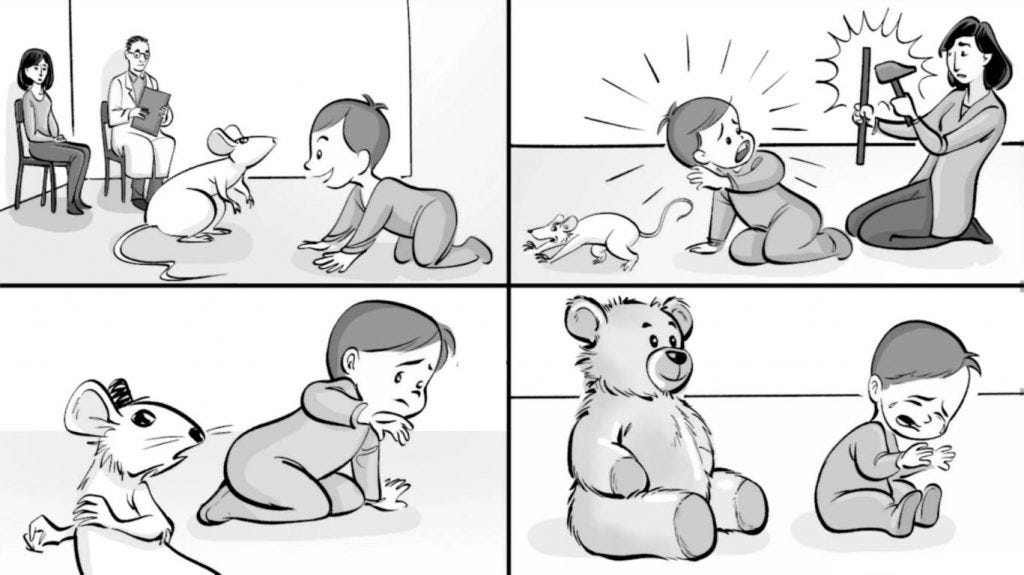

Bandura (1977, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023), developed the ‘social learning theory’, a combination of cognitive and social processes to decipher how observational learning occurs. Considering his theory, certain cognitive requirements must be present for behaviors to be imitated successfully. The observer is required to focus on the behavior, and it is more likely to be imitated if the observer can associate with the observed model and see themselves as equivalent to or of lower status than the model somehow. They will imitate the behavior only if they see themselves as competent enough. For example, if children see primary caregivers scream and run away at the sight of a mouse and they feel capable of doing so themselves, they might do the same. If they have the cognitive ability to store that experience in their memory, they will reproduce the behavior when seeing a mouse in the future without the presence of their caregiver. Furthermore, if the caregiver demonstrates a behavior and receives a reward in the form of comfort and attention from another grownup, the child might think if he behaves in a similar fashion, he might also be rewarded. This is an example of vicarious reinforcement, and it can be strengthened by positive reinforcement when repeating the behavior and being rewarded for the behavior in the future. Moreover, the phenomenon of learning via other media is called ‘informational transmission of fears’ (Rachman, 1977, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023). For example, people might watch a movie where a monster grabs someone from behind in the darkness and develops a fear of the dark, lygophobia. As a result, the social learning theory can explain how people develop phobias without directly experiencing a negative event. However, this can neither explain the non-random essence of phobias nor can the absence of phobias when experiencing a traumatic event (Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023).

The principles of social learning theory can be applied to the treatment of phobias. This is done by letting the observer pay attention to the model as they demonstrate calm behavior around the fear stimulus. This has been shown by Jones (1991, cited in Clayton, McFaul and Strathie, 2023), where he treated Little Peter, for fear of rabbits. He observed his friends playing happily with a rabbit and he was brought progressively closer to the rabbit over time using a technique called ‘degrees of toleration’. As a result, Little Peter overcame his fear of rabbits. However, the success of this treatment depends greatly on the confidence and capability of the model. In this way the social learning theory can be used to alter the expression of phobias.

In conclusion, it is clear to see how much behaviorists contributed to explain how and why phobias are attained and conveyed compelling evidence to support how the principles of classical conditioning and operant conditioning played a critical role in advancing the treatment of phobias. However, there are some shortcomings to the behaviorist’s approach. Not all phobias have their origins from a negative experience. Moreover, this approach can neither explain the non-random essence of phobias nor can it explain the absence of phobias when some people experience a traumatic event.

Reference:

Clayton, A., McFaul, C. and Strathie, A. (2023) ‘Fears and phobias’, in L. Lazard and A. Strathie (eds) Encountering psychology in context 1. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 273–314