This article will chronologically order the key milestones in the development of “thinking machines” and briefly comment on the implications of these advancements.

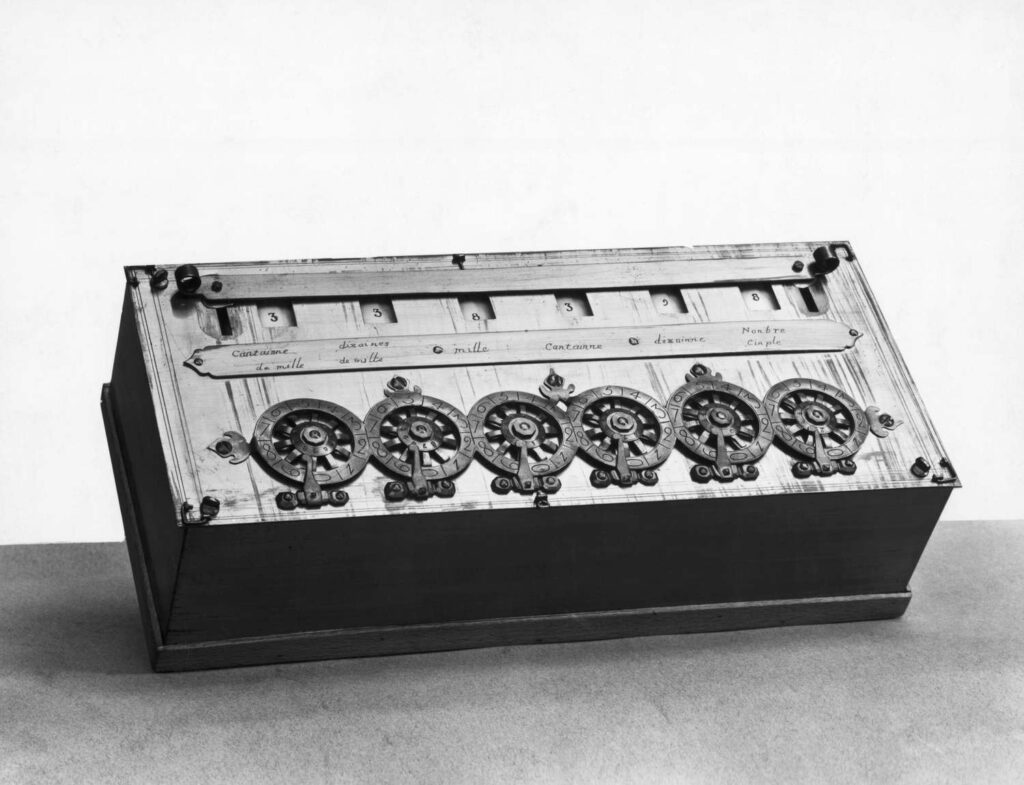

In the 17th century, there were two advancements that stood out. Between 1623 and 1662 a European mathematician, Blaise Pascal, invented the first calculating machine. A simple decimal calculator with ten rotating wheeled cogs (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). It was capable of addition and subtraction, but often broke down. This made humans realize that they can build machines to make daily mundane tasks easier for themselves. In 1689 Gottfried Leibniz discovered binary code, that is, that any number can be represented by a string of 1’s and 0’z (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). This discovery paved the way for modern day computer code programming.

In the 19th century Charles Babbage, and English mathematician designed a logarithmic calculator, the first ‘difference engine’ (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). He also designed a ‘universal machine’ that would be able to perform many calculations. This gave birth to modern day calculators that help humans to quickly and accurately do complex calculations. In addition, in 1847, George Boole realized that logical operations could also be represented in binary (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). Because mathematics, and solving complex calculations plays a huge role in computer science, one could argue that these discoveries opened the door for the development of modern-day computers and artificial intelligence.

By the 1950’s, computers that used binary states and coded instructions were being manufactured and used. Machines were starting to perform tasks like processes that simulated human intelligence, and this can be considered the birth of AI as a field of study (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). As a result, humans started relying more on machines to do certain tasks. In 1997, Deep Blue, a chess learning software beat the best chess player in the world, Garry Kasparov, for the first time. Turning proposed a question, “Can machines think?” and this is known as the Turning-test.

Since then, there have been many versions of the test, but they all have the same principle: “can computers respond to humans so that humans are convinced it is a human responding?”. Until now, no machine has successfully completed the Turning-test, however some passed parts of it. In 2014, a system called ‘Eugene’ was first to pass a version of the Turning test. The goal was to convince at least 30 per cent of human judges that it was human, and it convinced ten out of 30 of them (Choudhary, Erden, Turner, 2015). This remarkable advancement implies that AI development is progressing and is edging closer to the level of human intelligence, at least in some areas.

Advancements in AI brings upon an uncertain future for humans which is both exciting and terrifying at the same time. On the one hand, new advancements in many fields such as medicine, business, agriculture etc., that greatly benefit humans and on the other hand, giving birth to several ethical, moral and existential issues that are in their infancy and yet to be resolved.

References:

Choudhary, C., Erden, Y., Turner, J. (2015) Living Psychology: From the Everyday to the Extraordinary. 2nd edn. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 129-141